Because gunshot wounds to the head, particularly those resulting from high velocity projectiles, present differently than wounds to more elastic portions of the body, a brief look at wound ballistics is warranted. Wound ballistics is the study of projectile penetration of tissues. The mechanisms of tissue damage due to bullets include laceration or crushing and cavitation. Damage caused by cavitation is especially severe in gunshot wounds to the head. Since the contents of the skull are composed mostly of tissue and water, it is a rigid container filled with an incompressible material.

Understanding kinetic energy is the best way to grasp the physical factors associated with head gunshot wounds and their formation. The difference between impact velocity and residual velocity of the projectile forms the basis for calculating the kinetic energy expended in wound production. Kinetic energy increases in proportion to the velocity squared; hence the great wounding potential of high velocity projectiles. When the bullet ends its flight within the tissues, all the kinetic energy generated by the impact velocity is used in producing the wound. If a projectile does not exit the body, then all its kinetic energy is transferred to the tissues. If the projectile exits the body, then only a portion of its kinetic energy is transferred to the tissues.

Although velocity and mass determine the bullet's kinetic energy, its wounding potential relies on the efficient transfer of kinetic energy to tissues. Tissue resistance, demonstrated in elasticity and density, slows the projectile. This transfers kinetic energy to the surrounding structures, which are displaced backward, forward, and sideward, producing a temporary cavity or wound (8).

A missile's ability to produce a temporary cavity is considered an important component in wound production and degree of destruction (9). The temporary cavity may be considerably larger than the diameter of the bullet, and rarely lasts longer than a few milliseconds before collapsing into the permanent cavity or wound (bullet) track (10). Tissue from the permanent wound track is blown out in large quantities through spatter at the bullet entry and exit sites (11). This loss of tissues occurs in all high-velocity projectile penetrations (12) and perforations (13) (14).

The location of the wound impacts the resulting distribution of blood. Gunshot wounds may be widely varied in shape and diameter and may result in more bleeding in some areas of the body. The shape of the wounds, the severity of the damage and location of the injury is reflected in the different blood volumes disbursed.

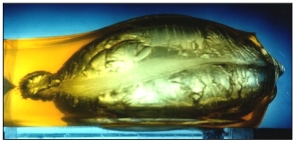

This is a photograph of a projectile traveling through

ballistic gel. A gunshot wound to a portion of the body that is elastic, such as

the abdomen, absorbs the temporary cavity produced and may result in small

well-defined entry and exit wounds. This may limit the volume of blood leaving

the body.

This is a photograph of a projectile traveling through

ballistic gel. A gunshot wound to a portion of the body that is elastic, such as

the abdomen, absorbs the temporary cavity produced and may result in small

well-defined entry and exit wounds. This may limit the volume of blood leaving

the body. The production of the temporary cavity is much more damaging to non-elastic tissue in the body, such as the brain or liver, where it commonly lacerates the tissue.

In gunshot wounds to the head, high velocity projectiles can produce a large wound surface (15). This is the result of the formation of the temporary cavity within the cranial cavity. Since the brain is encased by the closed and inflexible structure of the skull, only breaking the skull open can relieve the temporary cavity pressure. This produces a large wound surface for the release of blood. In lower velocity projectiles the temporary cavity may be much smaller and the skull may not have an explosive exit wound. However, no matter what size wound is present; the blood is expelled through entry and exit locations.

A temporary cavity produced in tissue that has been riddled by bullet fragments or bullet deformation causes a much larger permanent cavity by detaching tissue segments between the fragment paths. Thus projectile fragmentation can turn the energy used in temporary cavitation into a truly destructive force because it is focused on areas weakened by fragment paths rather than being absorbed evenly by the tissue mass (16).

A bullet interacts with the head in several stages (17).